What Does an Effective Audit Committee Actually Do? – Part 2

In Part 1 of this post, we considered the role and functions of the audit committee in overseeing risk management and internal controls, and monitoring the effectiveness of internal and external auditors. In this post, we explore the practical arrangements which make the audit committee successful.

Composition of the Audit Committee

The UK Code states that an audit committee should have at least 2 members who are independent non-executive directors (3 for listed companies). (i.e. they are not salaried employees, ex-employees or otherwise in a business relationship with the organisation). Appointments should be made by the Board in consultation with the Audit Committee chair. Usually appointments are made for 3 years, extendable for further periods. At least one member should have ‘recent and relevant financial experience’ and ideally a professional accountancy qualification. The role of the Chair is critical to success of the committee. A good chair will be independently minded, promote open discussion, manage meetings to cover all business and encourage a candid approach from all participants. An interest in and knowledge of financial and risk management, audit, accounting concepts and standards, and the regulatory regime are also essential. A specialism in one of these areas would be an advantage. Outside the formal meetings, the chair will usually meet periodically with the CEO, finance director, external auditor and head of internal audit, as well as the Chair of the Board.

The committee will need access to suitable resources to ensure agendas, board packs are distributed in advance and timely, accurate minutes are prepared. As a matter of good practice, the company secretary should normally act as secretary to the audit committee. Audit committee members must be given suitable induction and ongoing training, which should include understanding of financial statements, application of accounting standards, regulatory and legal developments affecting the organisation’s business, as well as risk management techniques. Internal and external auditors could usefully help with this as part of their retainer.

What makes an effective audit committee?

Recent research by Grant Thornton (Knowing the Ropes, 2015) found that the following qualities are found in effective audit committee members (ranked in order):

- Ability to ask challenging questions

- Recent and relevant financial experience

- Audit experience

- Ability to think clearly

- Experience from being an executive team member elsewhere

- Relevant industry background

- Good listening skills

- An eye for detail

- Experience of other audit committees

- Team-working skills

The FRC has recently proposed an amendment to its guidelines which recommends the audit committee should include competence relevant to the specific sector in which the organisation operates.

Some key questions which the audit committee should address include:

How do we know that there is a comprehensive process for identifying and evaluating key risks across the organisation and deciding what levels of risk are tolerable?

How do we know that the culture of risk management in the organisation is appropriate and how well people are supported to manage risk well?

How do we know how well the organisation identifies and reviews emerging and novel risks?

How do we know that the internal audit strategy is appropriate to deliver reasonable assurance on risk, controls and governance?

How do we know that accounting policies, financial management, and accounts are highlighting hidden financial risks?

How appropriate are the anti-fraud, whistle-blowing and conflicts of interest policies?

How do we know that management follows up on recommendations by auditors?

How do we know we are being effective in our work as a committee and making an impact on the organisation?

Running the audit committee

The audit committee chair should decide the timing and frequency of committee meetings, and the committee should meet as many times as the role and responsibilities require – typically there will be 3-4 meetings per year. FRC Guidance suggests the following:

- There should be at least 3 committee meetings per year, timed to coincide with key dates in the financial reporting and audit calendar, for example, to examine the audit plan before it commences, and to review the draft annual report and accounts before approval by the Board; to review the effectiveness of the audit process once it is complete.

- Sufficient time should be allowed between audit committee meetings and meetings of the main board to allow work arising from the committee to be carried out and reported to the Board as a whole.

- Only the audit committee chair and members are entitled to attend meetings of the committee. Salaried executives attend by invitation and may be asked to leave for certain items of business. It is usual for the Accounting Officer (usually the CEO) and Finance Director to attend regularly.

- At least once a year, the audit committee should meet the external and internal auditors, without management being present, to discuss its responsibilities and any issues arising from the audit.

- Work continues outside of formal meetings, with the Chair keeping in contact with key people such as the Board Chair, CEO , Finance Director, audit lead partner and head of internal audit.

It is very important to have a clear channel of communication between the audit committee and main Board. If the audit committee chair does not sit on the main board, it will be necessary to arrange for the chair of audit to meet with the Board to report on any findings and programme of work carried out. FRC Guidance recommends that the report should cover:

- Any significant issues found with the financial statements and how these were addressed

- An assessment of the effectiveness of external audit and recommendations on the selection, reappointment or removal of the auditor

- Issues where the Board has asked for the audit committee’s opinion

A typical cycle of meetings might be

Meeting 1

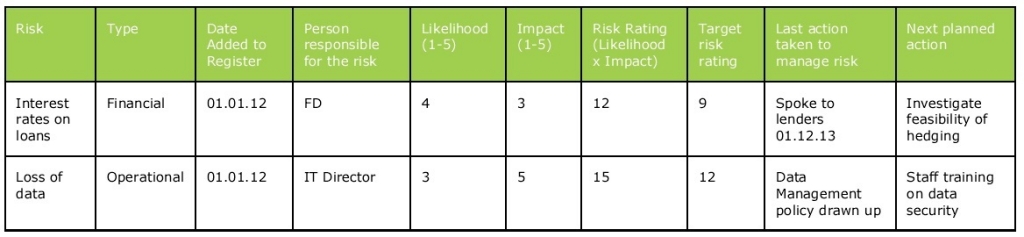

- approval of internal audit plan for following year in conjunction with review of risk register

- consideration of external audit pre-scoping report

- review of routine internal audit reports

Meeting 2

- presentation of draft accounts and statement of internal control

- review of external audit report on accounts

- review of annual internal audit report for year

- review of other assurance reports for year

- review of risk register

Meeting 3

- post audit effectiveness review

- review of routine internal audit reports

- review of strategic and operational risk registers

- ‘deep dive review’ of a key risk area

Meeting 4

- review of routine internal audit reports

- review of risk registers

- ‘deep dive review’ of a key risk area

Strive for continuous improvement

Audit Committees should assess their performance annually. Typically, this review will cover areas such as reviewing and, if necessary, updating their terms of reference, assessing whether sufficient resources have been deployed to support their activities, the effectiveness of meetings, procedures for induction, training and succession planning, and the quality and value of internal and external audit activities. An external review can help to bring an independent perspective. The Committee should draw up its own plan for improvement as a result of the self-assessment, either requesting future training or development for members, or in changes to its processes and procedures.

Final thoughts

Audit Committees have a crucial role to play in the governance of any organisation – unless they report effectively on the relevance and rigour of the underlying structures and processes and on the assurances that the Board receives, the entire governance framework can be compromised. Effective audit committees provide comfort and reassurance to senior managers, ensuring that the organisation has a sound base for growth and protection against nasty surprises. Audit Committee members must therefore take responsibility for scrutinising the risks and controls affecting every aspect of the business. Whilst the role of an Audit Committee member is demanding, it can also be an enriching and rewarding experience.

If you need help in establishing an audit committee, an independent review of its effectiveness or advice on any other aspect of corporate governance, please get in touch.

Mark Johnson is an experienced solicitor & chartered company secretary supporting businesses, charities, social enterprises & academy trusts on governance, compliance & legal affairs. He also serves as an independent audit committee member for a leading Multi-Academy Trust. Please get in touch info@elderflowerlegal.co.uk or 01625 260577.

If you would like to be kept up to date on more topics like this, then why not sign up to receive our regular newsletter.