Relentless Focus on Good Governance in Academies Continues

Good Governance in Academies is Key Focus for DfE

Over the Summer the Department for Education quietly published some documents which show the focus on good governance in academies remains a key priority. The first document was the widely expected new edition of the Academies Financial Handbook which applies from 1 September. Secondly, the Education and Skills Funding Agency (the new name for the EFA) published three financial management and governance reviews into multi academy trusts. These highlight case studies of where things can go wrong. In case you missed them, here we summarise the key points to be aware of.

Academies Financial Handbook

It is a requirement of all Academy Trusts’ Funding Agreements that the Academies Financial Handbook (’AFH’) is complied with, in particular the list of ‘must haves’ in Annex C. The new AFH applies as from 1 September 2017. The main changes in this new edition concern governance and financial control.

Governance

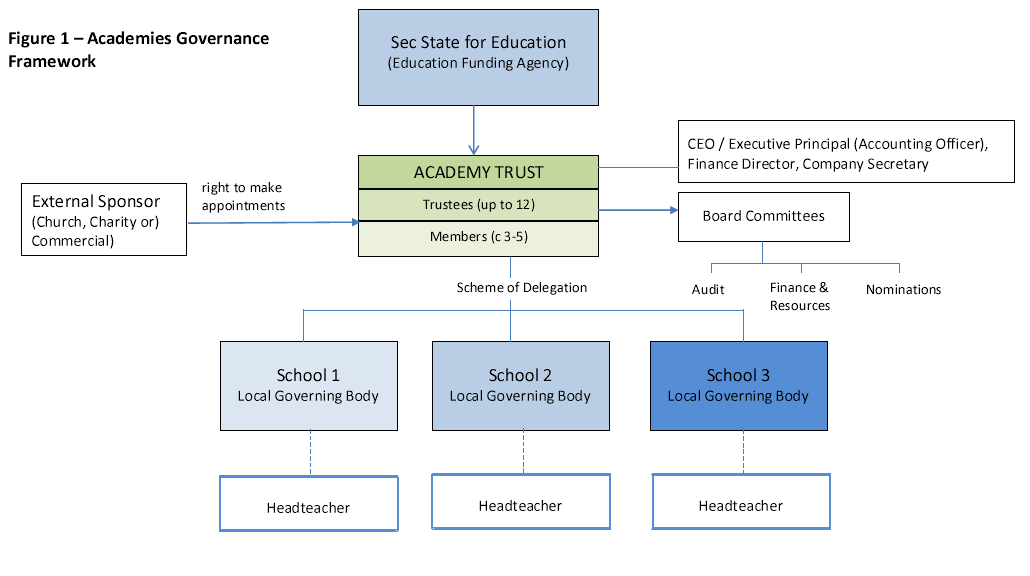

- There is an emphasis on greater clarity about the roles of members, trustees and salaried employees

There must be clear separation between the roles of member, trustees and executive (paid) managers. For example, employees of the Trust must not be appointed as members, unless permitted by the Articles of Association. The current model articles do not allow members to be employees, but some older versions do. Trusts with older articles may wish to consider revising their articles to reflect best practice.

In addition, the DfE’s preference is that no other employees, other than the Senior Executive Leader, should serve as a trustee. This helps to ensure there are clear lines of accountability through the Senior Executive Leader. Older Articles may talk about no more than one third of trustees being employees. Again, Trusts may wish to adopt this change in line with best practice.

- Trusts are reminded that the overarching seven Nolan principles of public life apply to everyone holding office in an Academy trust (selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership).

- Annual letters to Trusts’ Accounting Officers/CEOs from the ESFA’s accounting officer must be discussed by the Board and appropriate action taken

The ESFA sends letters to Trusts’ Accounting Officers/CEOs from time to time which cover issues pertinent to their role and ESFA reviews. The letter must now be shared with members, trustees, Chief Financial Officer and other members of the senior leadership team. It must be discussed by the Board of trustees. This discussion should be clearly documented in the Trust board minutes. All “Dear Accounting Officer” letters can be found on the DfE website here.

- Improving efficiency and value for money in academy trusts

Where the ESFA have concerns about a Trust’s financial management, but not enough to issue a Financial Notice to Improve (FNtI), they may require the Trust to work with an expert in school financial health and efficiency to support the Trust and identify where improvements can be made. They may also prescribe this as a condition of a FNtI.

- There is an emphasis on the importance of addressing skills gaps on the Board at key transition points such as growth periods. Trusts are recommended to use the DfE’s competency framework for governance to determine skills gaps in the Board (see more here)

- Trusts should consider the key features of effective governance in the DfE’s Governance Handbook when assessing their effectiveness

Boards should be looking to implement these as part of their annual assessment of their effectiveness and skill-set, as well as minuting these discussions.

- Edubase must be kept up to date with details of changes to Trustees and members within 14 days

Recent ESFA reports have highlighted that some Trusts are not keeping their records up to date of who are members and trustees promptly following either appointments or resignations. This applies to both Edubase and Companies House records. Someone should be given specific responsibility to complete this task, usually the Company Secretary.

- Appointment of auditors must be approved by the members, not just the trustees

The Board of trustees may believe they are responsible for the appointment of auditors. However, this is only the case where the Companies Act permits trustees to appoint them e.g. in the Trust’s first accounting period. Thereafter the members must approve the appointment, usually at an AGM.

Financial Control

- a new section on executive pay states that Boards must ensure their decisions on levels of pay follow a robust evidence-based process and reflect the roles and responsibilities of individuals

The decisions should be backed up with supporting evidence and secure records kept–such as confidential appendices to minutes.

- ‘Repercussive transactions’ as well as ‘novel or contentious transactions’ now require ESFA approval

Repercussive transactions are those which are likely to cause pressure on other trusts to take a similar approach and hence have wider financial implications for the academies sector.

- Clarification that the non-statutory/non-contractual element of a severance payment limit of £50,000 is based on the gross amount before any deductions for tax etc.

This is a welcome technical clarification. The full new Handbook can be viewed here.

Financial Management and Governance Reviews

The ESFA can initiate a Financial Management and Governance review at an academy trust following a complaint, or on its own initiative, either at random or as part of its new routine assurance activities. There have been 25 such reviews conducted since 2013. The typical remit of a review is:

- to assess the financial controls and management in a Trust to see if they are compliant with the AFH and Funding Agreement

- to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of governance, risk management and internal controls

- to assess propriety, regularity and value for money

The ESFA’s policy is to publish their findings to inform public debate and scrutiny. The academy trust is usually given 5 working days to comment on the report before it is published. Three such reports were published over the Summer.

The first review concerns the DRB Ignite MAT. The review was instigated following a complaint about a leasing arrangement for whiteboards at one of their schools. However, the remit soon expanded to cover scrutiny of wider governance arrangements in the MAT. The key findings of the review were:

- There was a lack of separation of the roles of members, trustees and executive managers. The Accounting officer was a member as well as being a director. The Accounting Officer was not on the Trust’s payroll and the role had rotated among the directors three times. There was no written agreement in place setting out the role and responsibilities of the Accounting officer – in breach of the Academies Financial Handbook. The AFH requires that the role be allocated to a Single Executive Leader, who is accountable for the use of public money. The CFO role was contracted out to another group company and the Trust board did not have any independent directors with accountancy experience or qualifications. This created a risk of inadequate oversight and challenge. The named member of the trust was a company which had since become dormant, thereby breaching the Articles of Association.

- The trust was using related commercial companies and connected parties to provide 83% of its central functions and expenditure without following a proper procurement process. Remember that delivery of services by related parties can only be ‘at cost’ (see below) and a contract for services or goods may need to advertised and comply with EU procurement rules if over a threshold of £164,176 (unless it can be argued that by their nature the services fall under the Light Touch Regime in which case a higher threshold of £589,148 may apply). The ESFA was not satisfied that adequate procedures were in place to manage conflicts of interest between the Trust and connected companies. The same people sat on the Trust board and the boards of group companies providing the services. Directors were approving invoices from their own group companies for payment. This was potentially a breach of Companies Act duties and charity law, as well as the AFH.

- The award of a contract for smartboards at one of the trust’s primary schools to a group company did not follow best practice and could not demonstrate value for money

- The trust had failed to keep EduBase updated with details of members and trustees within 14 days.

- There was no central of register of contracts, making it difficult to coordinate the re-tendering to drive value for money

- There was a failure to publish details of business and pecuniary interests of trustees on the website and failure to keep adequate minutes of trustee meetings.

The Trust was ordered to undertake a review of its governance arrangements and carry out urgent corrective actions.

The second review was published on 28 June and concerned the Rodillian MAT. The investigation was triggered by complaints about the Accounting Officer staying at a luxury hotel several nights a week, despite living within travelling distance of the schools. The review quickly broadened in scope and found other issues which are documented in the ESFA report:

- The Accounting Officer had been reimbursed for hotel accommodation – although there was no policy on approved subsistence and travel in place to measure the reasonableness of this and no evidence of Board approval for the expenditure

- The trust had rented a flat for the Accounting Officer – although the benefit was not documented – this should have been regarded as a novel or contentious payment and ‘ex gratia’ benefit for which ESFA approval was required

- The Trust had awarded a contract worth £1.45m for alternative education for students excluded from mainstream provision without following a competitive tendering procedure. Although the contract was for 5 years, the liability in the accounts was only shown as a 3 year commitment.

- The Trust did not have an up to date financial procedures manual in place

- There were no proper procedures for authorising payments to suppliers

- The Trust had entered into supposed ‘operating leases’ of smart boards which were in fact ‘finance leases’ (which require prior approval from ESFA).

- The Trust Chair was paid for consultancy services – as the Chair was also a member this is not allowed and would have required prior consent from the Charity Commission.

The third review concerned Enquire Learning Trust. According to the report, similar themes came to light:

- Senior managers were employed ‘off payroll’ through limited companies

- There was lack of skills and oversight of managers by the Trust Board

- The role and responsibilities of the Accounting Officer were not documented in a contract

- The financial reports presented to the board were inadequate and did not give trustees a picture of the overall consolidated financial position of the trust. There was no 3-5 year consolidated forecast.

- Two significant related party transactions in 2015/16 were not disclosed

- Financial controls over purchasing, including the use of corporate credit cards were inadequate. The lack of segregation of duties and independent oversight of purchasing and payment arrangements increased the risk of inappropriate expenditure.

- Trust officers had claimed irregular payments for valuations of trust premises in connection with a scheme to transfer the Trust premises into their personal pension funds and lease it back to the Trust

- There was no central asset register to keep track of valuable items such as laptops issued to staff

- There was no audit committee or independent Responsible Officer to carry out assurance checks

Lessons to be learned

A complaint can be triggered by a disgruntled employee or governor – once the process starts it can be very resource intensive to manage and the scope of the inquiry can quickly widen.

- Understanding the separation of roles between members, trustees and executive managers is absolutely critical. A clear Scheme of Delegation, Code of Conduct, policies and procedures are your first line of defence in demonstrating compliance. Be clear about who your members are and keep the register up to date so it is clear who actually holds the voting rights. Make sure they are involved in relevant key decisions and due process is followed.

- Remember the ‘at cost’ requirement if awarding contracts to a ‘connected party’. An individual or company can supply good and/or services up to £2,500, cumulatively, in any financial year which can include profit; however, beyond £2,500, all transactions must be ‘at cost’ without profit. Where ‘at cost’ is triggered, a statement of assurance is required from the supplier to support the arrangement, which the Accounting Officer must review to ensure that there are no issues with the transaction. ‘Connected parties’ include members, trustees, sponsors (as well as their family members and business associates).

- Develop a set of Standing Orders and Financial Regulations which set out the requirements for obtaining competitive quotes, authorisations for expenditure, delegated limits and the limited circumstances in which this can be waived. Remember that contracts with a value in excess of £164,176 may be subject to EU competitive tendering rules.

- Be very careful about awarding contracts to ‘connected parties’. These will almost always be spotted during the external audit and will be flagged up in your annual accounts attracting further scrutiny. The Articles of Association will usually set out the process which must be followed to properly authorise such a transaction – any trustees with an interest in the contract must declare this and must withdraw from the meeting.

- Develop a set of policies on subsistence and accommodation expenses, gifts and hospitality so that everyone knows where the boundaries are.

- “Off payroll arrangements” – whilst there may be the odd time such arrangement is appropriate, for standard roles payments should be on-payroll, which also helps ensure that the individual is meeting their tax obligations.

- Make sure that novel and contentious issues go to the Board for discussion and that decisions and the justification for them are properly minuted.

- Understand the difference between finance leases and operating leases . Under an operating lease all risks and rewards related to asset ownership remain with the lessor for the leased asset. In this type of lease, the asset is returned by the lessee after using it for lease term agreed upon. The ownership of the asset remains with the lessor. However, under a finance lease the risks and rewards related to ownership of asset leased are transferred to the lessee. The lessee usually has an option to acquire ownership at the end of the lease by making a further payment. In accounting terms, this is usually treated like a loan.

- If these Trusts had had an effective Audit Committee providing oversight and challenge, these situations could probably have been avoided. As one review commented: “Audit Committee functions should be established in such a way as to achieve internal scrutiny that delivers objective and independent assurance. Where the Responsible Officer function is provided by [a group company] it cannot be shown to be independent and hence is in breach of the Academies Financial Handbook”. See more on the role of an Audit Committee.

- It is always good practice to take a step back before entering into any unusual transactions and consider the wider implications. Could this transaction attract adverse media coverage? Is it outside our normal business activity? If we enter into the transaction and another academy trust hears of this, will it impact upon the wider sector? Whilst this comes down to judgement and perception, it may be safest to consult with ESFA before performing the transaction rather than being criticised later for making the wrong decision.

- Consider undertaking a governance review facilitated by an external provider to check your house is in order and that you are following best practice. We offer a fixed price service GovernanceCHECK360.