Crafting a Winning Strategy: What’s the Secret Sauce?

One of the key tasks of any Board in the private, not-for-profit or public sector is to create a strategy for their organisation. Strategy is inextricably linked to good governance and effective risk management. The UK Corporate Governance Code at C.1.2: “Directors should include in their annual report an explanation of the strategy for delivering the objectives of the company.” Strategy has been defined as “the direction and scope of an organisation over the long-term which achieves advantage in a changing environment through its configuration of resources and competencies, with the aim of fulfilling stakeholder expectations[1]”. For businesses, a winning strategy should provide a sustainable competitive advantage. For other types of organisation, the strategy provides a mechanism to seek an increased share of limited resources, with the aim of advancing a mission, whilst balancing the interests of different stakeholders.

What is an effective strategy?

Creating a successful strategy is not an easy task. It is completely different to operational management. It requires board members to set aside proper creative thinking time, question assumptions and develop a critical enquiring approach. It can’t be achieved by a solo actor working in an ivory tower: it requires contribution and buy-in from a wider group of leaders and senior managers. The statistics show that most boards do not get it right. Studies published by Harvard Business Review show that at least 70% of strategies fail. Some research has found that 85% of directors don’t know what their organisation’s source of competitive advantage is. In his 2011 book, Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, Rumelt tells us that a winning strategy contains three elements: a diagnosis, which defines the nature of the challenge, a guiding policy to overcome the obstacles identified which builds on or creates some form of advantage and (iii) a set of coherent actions coordinated with each other to accomplish the guiding policy. Typically, insufficient time is spent on diagnosis, as managers rush to action; sometimes the actions are not coherent because of a lack of alignment.

Why do most strategies fail?

Rumelt identifies four hallmarks of bad strategy, which we can all recognise: the use of ‘fluff’ (gibberish and buzzwords masquerading as strategic concepts to give the impression of intellectual thinking!); failure to define the real challenge, mistaking a long list of aspirational goals for strategy (e.g. we will grow our revenue by 20%, we will delight our customers etc, without saying how); setting objectives which are just impracticable in the context of the organisation, or which fail to address critical weaknesses in resources and capabilities.

So how do we avoid falling into this trap? Here I offer a ten point plan from my experience which could be used to help develop a winning strategy.

- Start with why?

Simon Sinek has developed a whole business methodology around this question. We first need to understand the motive force behind the enterprise. Why are you in business, what is your core purpose and mission? Has this been explicitly captured and communicated to all your stakeholders? When did you last review it?

- Values matter more than ever

Identify what the values of the organisation are and how these reflect your culture (the beliefs, traditions and habits shared by your people). Capturing the values requires input from across the organisation. Values can be used to set the ethical and legal boundaries for the activities you undertake and to set the emotional temperature of the organisation. However, it is no use articulating a charter if those at the top do not lead by example! Studies show that the Generation Y millennials and Generation Z among your customers and employees are particularly attuned to corporate values- ignore them at your peril.

- Assess your current position

Use a SWOT analysis to assess strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats facing the organisation. Strengths and weaknesses are normally internal factors, whilst opportunities and threats are external forces. Strengths might include specialist knowledge, a highly skilled workforce; weaknesses might include a lack of working capital or inefficient operating procedures. In looking at external forces, it is useful to employ the PESTEL analysis to identify the political, economic, sociological, environmental and legal factors that could, or do already, impact on your business environment. From this analysis, identify the top 3-5 critical success factors – the essential factors which the organisation must absolutely get right to succeed and keep these front of mind.

- Where else could you play?

Having identified your strengths and some opportunities, in which markets (existing, new or adjacent) could you operate? For example, if you were an enterprise with strengths in residential care for the elderly, could you move into caring for learning disabilities? What discontinuities could occur which could open up new avenues of opportunity for you?

- What is the structure of competition in your markets?

Use Michael Porter’s Five Forces model to assess the structure of competition in your chosen markets. Porter identifies 5 forces which influence market position:

(1) current competitive rivalry – if there is strong competition this will drive prices down and increase costs for businesses trying to compete

(2) Is there potential for entry of new competitors? How easy would it be for new competitors to emerge – are there factors under your control which could prevent or delay this, such as a well-defined brand identity, differentiated products or services, exclusive IP rights that you own?

(3) Power of the customer – the customer tends to have power if their purchasing power is concentrated (e.g. through buying frameworks), or if the product or service is seen as undifferentiated;

(4) Power of your suppliers – they may enjoy power over you because of high switching costs or because there are few alternatives;

(5) The threat of substitutes – are there other ways of solving the customer’s problem besides coming to you? Being alert to innovation that could be a complete game-changer is important. If competitive pressure is becoming too great, it may be time to move into more attractive markets where demand exceeds supply, margins are better and the pressure is manageable.

- What are your distinctive competencies and capabilities?

Your capabilities are derived from your people, financial capital, materials, technology, information and knowledge, buildings and intangibles such as brand, reputation, IP rights and leadership. Barney tells us that to provide real competitive advantage capabilities should ideally be valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable. This allows you to differentiate your products and services from the competition.

- How do your activities create value for the customer?

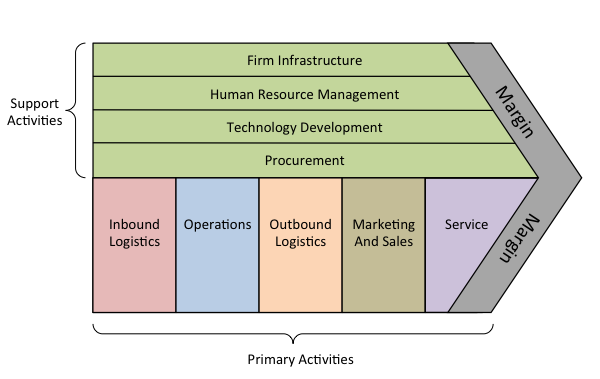

A useful tool to examine the value added in each stage of your operations is Porter’s value chain. In essence, he divides an organisation’s activities into strategically relevant activities and supporting or ‘back office’ activities. In the strategically relevant activities, we find inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales and ‘after sales’ service. These labels can be adapted to suit the particular context.

For example, in a service environment, instead of inbound logistics, we may find customer enquiries, brochures, whitepapers etc. Operations would be the way projects are managed and delivered. In the supporting activities we find HR management, technology, procurement and the general infrastructure of the enterprise.

By taking each element, and forensically considering how it is performed and how it can be improved, you should be able to reduce cost or add more value for the customer and differentiate your offer. This is where ideas and innovations from front-line staff can really come to the fore. Do you have mechanisms to encourage and capture these ideas?

Having analysed the areas above, we should by now have a set of choices to consider. It is time to…

- Carry out a sense check

Applying the test formulated by Johnson et al, are the options suitable, feasible and acceptable? Suitability tests whether the strategy fits the vision and mission of the organisation. Does it leverage the strengths and minimise the weaknesses? Feasibility is concerned with whether the organisation has the right financial, human and information resources, culture and structure to pursue the strategy. Finally, acceptability tests whether the strategy fits with the risk appetite of the organisation and whether it is likely to find favour with your stakeholders, such as employees, suppliers and funders?

- Set Objectives

Having formulated the strategy, embody this in a set of concrete objectives which should be SMART objectives (specific, measurable, agreed, realistic and time-bound). Ensure the high level objectives cascade down to business units and individual performance goals across the organisation. Make sure there is clear ownership of and accountability for the agreed objectives.

- Align the organisation

The chosen strategy will have implications for every function in the organisation, including finance, operations, marketing, HR and technology Alignment is crucial to achieve success. It is no good setting high level objectives which are completely at odds with teams’ or individuals’ performance and remuneration criteria or which run counter to the existing culture of the organisation.

Once the plan is developed and resources are committed, be tough and persistent in applying it. Ensure there are consequences for not delivering. The methodology behind successful implementation will be the subject of a future piece.

Of course these tools and models alone do not give directors the right answer, but they do provide the means to have a better conversation, which leads on to the agreed answer. By using these techniques, you can create an effective planning process, build a realistic business direction for the future, and should greatly improve the chances for successful implementation of your strategy.

In Part 2: how to implement your strategy successfully to differentiate your organisation from the competition.

[1] (Johnson, Scholes et al, 2011).